| Title |

2006-1 Partners for Progress-Uncommon Vision Keepsake |

| Creator |

Weber State Univesity |

| Contributors |

Utah Construction Company/Utah International |

| Description |

The WSU Stewart Library Annual UC-UI Symposium took place from 2001-2007. The collection consists of memorabilia from the symposium including a yearly keepsake, posters, and presentations through panel discussions or individual lectures. |

| Subject |

Littlefield, Edmund W. (Edmund Wattis), 1914-2001; Eccles, Marriner S. (Marriner Stoddard), 1890-1977; Utah Construction Company; Utah International Inc. |

| Digital Publisher |

Stewart Library, Weber State University, Ogden, Utah, USA |

| Date Original |

2006 |

| Date |

2006 |

| Date Digital |

2008 |

| Temporal Coverage |

2001; 2002; 2003; 2004; 2005; 2006; 2007 |

| Item Size |

7 inch x 7 inch |

| Medium |

books |

| Item Description |

92 page paperback book |

| Type |

Text; Image/StillImage |

| Conversion Specifications |

Archived TIFF images were scanned with an Epson Expression 10000XL scanner. Digital images were reformatted in Photoshop. JPG and PDF files were then created for general use. |

| Master Quality |

400 PPI |

| Language |

eng |

| Relation |

https://archivesspace.weber.edu/repositories/3/resources/212 |

| Rights |

Materials may be used for non-profit and educational purposes; please credit Special Collections Department, Stewart Library, Weber State University. |

| Source |

HD9715.U54U88 2006 Special Collections, Stewart Library, Weber State University |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s6ksyej5 |

| Setname |

wsu_ucui_sym |

| ID |

97633 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s6ksyej5 |

| Title |

2006_026_page42and43 |

| Creator |

WSU Stewart Library |

| Image Captions |

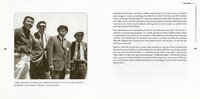

During World War II, Ed Littlefield served in the Petroleum Administration office in Washington, D.C., placing him in proximity to Marriner Eccles, left, governor of the Federal Reserve System, and shown here with President Roosevelt and his son, James Roosevelt. |

| Description |

The WSU Stewart Library Annual UC-UI Symposium took place from 2001-2007. The collection consists of memorabilia from the symposium including a yearly keepsake, posters, and presentations through panel discussions or individual lectures. |

| Subject |

Edward Littlefield, Marriner Eccles, Ogden-Utah, Utah Construction Company, Utah International |

| Date Original |

2006 |

| Date |

2006 |

| Date Digital |

2008 |

| Item Description |

92 page paperback book |

| Type |

Text; Image/StillImage |

| Conversion Specifications |

Archived TIFF images were scanned with an Epson Expression 10000XL scanner. Digital images were reformatted in Photoshop. JPG and PDF files were then created for general use. |

| Master Quality |

400 PPI |

| Language |

eng |

| Rights |

Materials may be used for non-profit and educational purposes; please credit Special Collections Department, Stewart Library, Weber State University. |

| Source |

HD9715.U54U88 2006 Special Collections, Stewart Library, Weber State University |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Setname |

wsu_ucui_sym |

| ID |

97886 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s6ksyej5/97886 |