| Title |

018_Pioneer Histories Compiled by Mount Joy Camp (DUP Book 15) |

| Creator |

Smith, Bertie |

| Contributors |

Daughters of Utah Pioneers, Morgan County |

| Description |

In the early part of the 1900s Daughters of Utah Pioneers historians interviewed pioneers and their children and wrote or gathered the histories. |

| Biographical/Historical Note |

These histories were read in Mt. Joy D.U.P. Camp meetings between 2008 and 2010. Circa 2017, additional histories of Morgan pioneers, not seen before, were left in the museum or sent to the museum by descendants of the pioneers. These were verified and then gratefully accessioned into the museum's collection as part of Book 15. The histories were digitized in 2017 and archived in the Morgan County D.U.P. Pioneer Memorial Building. |

| Subject |

Morgan County (Utah)--History; Mormon pioneers; Mormons--Utah |

| Digital Publisher |

Stewart Library, Weber State University, Ogden, Utah, USA |

| Date Original |

2006; 2007; 2008; 2009; 2010 |

| Date |

2006; 2007; 2008; 2009; 2010 |

| Date Digital |

2017 |

| Temporal Coverage |

1830; 1831; 1832; 1833; 1834; 1835; 1836; 1837; 1838; 1839; 1840; 1841; 1842; 1843; 1844; 1845; 1846; 1847; 1848; 1849; 1850; 1851; 1852; 1853; 1854; 1855; 1856; 1857; 1858; 1859; 1860; 1861; 1862; 1863; 1864; 1865; 1866; 1867; 1868; 1869; 1870; 1871; 1872; 1873; 1874; 1875; 1876; 1877; 1878; 1879; 1880; 1881; 1882; 1883; 1884; 1885; 1886; 1887; 1888; 1889; 1890; 1891; 1892; 1893; 1894; 1895; 1896; 1897; 1898; 1899; 1900 |

| Item Size |

10x11.5 inches |

| Medium |

histories |

| Item Description |

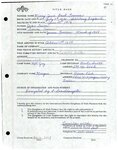

3-ring binder. This book contains 28 typewritten pioneer histories and documents on 185 pages, housed in page protectors. Some of the pages contain handwritten title pages. |

| Spatial Coverage |

Morgan County, Utah, United States, http://sws.geonames.org/5778525/ |

| Type |

Text |

| Conversion Specifications |

JPG images were scanned with a Kodak PS50 scanner. Transcription using ABBYY Fine Reader. PDF files were created for general use. |

| Language |

eng |

| Rights |

Materials may be used for non-profit and educational purposes; please credit Morgan County Daughters of Utah Pioneers, Morgan, Utah. |

| Source |

Daughters of Utah Pioneers, Morgan County |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s6pa4h1s |

| Setname |

wsu_mdupc |

| ID |

47866 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s6pa4h1s |