| Title |

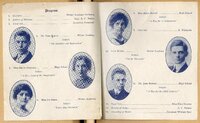

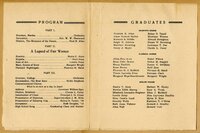

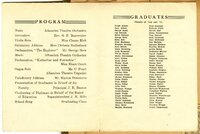

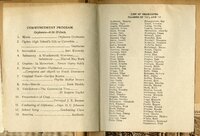

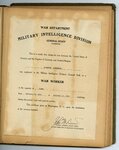

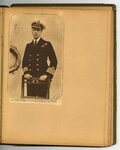

1908-1937 Florence Zimmerman Ogden High School Scrapbook |

| Creator |

Ogden High School |

| Contributors |

Ogden High School Students |

| Description |

Over the past 100 years, students at Ogden High School have been creating scrapbooks. These books document the memories of the students each year. The scrapbooks hold a snapshot and time capsule of each student body. Each one contains photographs, newspaper articles and a written yearly history. |

| Subject |

Students.; Education; Ogden (Utah); Ogden High School |

| Digital Publisher |

Stewart Library, Weber State University, Ogden, Utah, USA |

| Date Original |

1908; 1909; 1910; 1911; 1912; 1913; 1914; 1915; 1916; 1917; 1918; 1919; 1920; 1921; 1922; 1923; 1924; 1925; 1926; 1927; 1928; 1929; 1930; 1931; 1932; 1933; 1934; 1935; 1936; 1937 |

| Date |

1908; 1909; 1910; 1911; 1912; 1913; 1914; 1915; 1916; 1917; 1918; 1919; 1920; 1921; 1922; 1923; 1924; 1925; 1926; 1927; 1928; 1929; 1930; 1931; 1932; 1933; 1934; 1935; 1936; 1937 |

| Date Digital |

2016 |

| Temporal Coverage |

1908; 1909; 1910; 1911; 1912; 1913; 1914; 1915; 1916; 1917; 1918; 1919; 1920; 1921; 1922; 1923; 1924; 1925; 1926; 1927; 1928; 1929; 1930; 1931; 1932; 1933; 1934; 1935; 1936; 1937; 1938; 1939; 1940; 1941; 1942; 1943; 1944; 1945; 1946; 1947; 1948; 1949; 1950; 1951; 1952; 1953; 1954; 1955; 1956; 1957; 1958; 1959; 1960; 1961; 1962; 1963; 1964; 1965; 1966; 1967; 1968; 1969; 1970; 1971; 1972; 1973; 1974; 1975; 1976; 1977; 1978; 1979; 1980; 1981; 1982; 1983; 1984; 1985; 1986; 1987; 1988; 1989 |

| Item Size |

12.5 x 9.75 x 1.5 inch |

| Medium |

scrapbooks |

| Item Description |

Burlap covered scrapbook with the word SCRAPS and some flowers styalized on the front. 30 pages, most used front and back. |

| Spatial Coverage |

Ogden, Weber County, Utah, United States, http://sws.geonames.org/11788968, 41.22809, -111.96766 |

| Type |

Text; Image/StillImage |

| Conversion Specifications |

TIFF images were scanned by Erich Goeckeritz with an Epson Expression 10000XL scanner. OCR by Alexandra Park using ABBYY Reader. JPG and PDF files were then created for general use. |

| Language |

eng |

| Rights |

Digital image copyright 2015, Ogden High School |

| Sponsorship/Funding |

Available through grant funding by the Utah State Library and the Institute of Museum and Library Services. |

| Source |

Ogden High School Library |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s6kfzwvb |

| Setname |

wsu_ohss |

| ID |

73474 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s6kfzwvb |

| Title |

Page 11 - OHS_Zimmerman013 |

| Creator |

Ogden High School |

| Contributors |

Ogden High School Students; Available through grant funding by the Utah State Library and the Institute of Museum and Library Services. |

| Description |

Over the past 100 years, students at Ogden High School have been creating scrapbooks. These books document the memories of the students each year. The scrapbooks hold a snapshot and time capsule of each student body. Each one contains photographs, newspaper articles and a written yearly history. |

| Subject |

Students.; Education; Ogden (Utah); Ogden High School |

| Digital Publisher |

Stewart Library, Weber State University |

| Date Original |

1908; 1909; 1910; 1911; 1912; 1913; 1914; 1915; 1916; 1917; 1918; 1919; 1920; 1921; 1922; 1923; 1924; 1925; 1926; 1927; 1928; 1929; 1930; 1931; 1932; 1933; 1934; 1935; 1936; 1937 |

| Date |

1908; 1909; 1910; 1911; 1912; 1913; 1914; 1915; 1916; 1917; 1918; 1919; 1920; 1921; 1922; 1923; 1924; 1925; 1926; 1927; 1928; 1929; 1930; 1931; 1932; 1933; 1934; 1935; 1936; 1937 |

| Date Digital |

2016 |

| Temporal Coverage |

1908-1989 |

| Item Description |

12.5in. X 9.75in. X 1.5in. Burlap covered scrapbook with the word SCRAPS and some flowers styalized on the front. 30 pages, most used front and back. |

| Spatial Coverage |

Ogden, Weber County, Utah, United States, http://sws.geonames.org/11788968, 41.22809, -111.96766 |

| Type |

Text; Image |

| Conversion Specifications |

TIFF images were scanned by Erich Goeckeritz at 400 DPI with an Epson Expression 10000XL scanner. OCR by Alexandra Park using ABBYY Reader. JPG and PDF files were then created for general use. |

| Language |

eng |

| Rights |

Digital image copyright 2015, Ogden High School |

| Source |

Ogden High School Library |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Setname |

wsu_ohss |

| ID |

74471 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s6kfzwvb/74471 |