| Title |

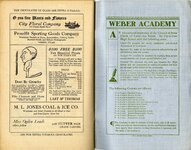

1909 The Acorn Vol. 7 No. 2 December |

| Creator |

Weber Academy |

| Contributors |

Students of Weber Academy |

| Description |

The Acorn is a bi-monthly literary magazine published by the students of Weber Stake Academy and Weber Academy from 1904 to 1916. |

| Subject |

Students; Forms, Literary; College students--Education; Ogden (Utah); Weber Stake Academy; Weber Normal College; Weber College; Weber State College |

| Digital Publisher |

Stewart Library, Weber State University |

| Date Original |

1909 |

| Date |

1909 |

| Date Digital |

2013 |

| Item Description |

6 x 9.25 in. paperback. Pages number 1-36. |

| Type |

Text |

| Conversion Specifications |

Archived TIFF images were scanned at 400 dpi with an Epson Expression 10000XL scanner. OCR done with ABBYY Reader. JPG and PDF files were created for general use. |

| Language |

eng |

| Rights |

Public Domain. Courtesy of University Archives, Stewart Library, Weber State University |

| Source |

Archives LH1.A185 |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s6f0vpnv |

| Setname |

wsu_olp |

| ID |

76718 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s6f0vpnv |

| Title |

009_page 6 and 7 |

| Creator |

Weber Academy |

| Contributors |

Students of Weber Academy |

| Description |

The Acorn is a bi-monthly literary magazine published by the students of Weber Stake Academy and Weber Academy from 1904 to 1916. |

| Subject |

Students; Forms, Literary; College students--Education; Ogden (Utah); Weber Stake Academy; Weber Normal College; Weber College; Weber State College |

| Digital Publisher |

Stewart Library, Weber State University |

| Date Original |

1909 |

| Date |

1909 |

| Date Digital |

2013 |

| Item Description |

6 x 9.25 in. paperback. Pages number 1-36. |

| Type |

Text |

| Conversion Specifications |

Archived TIFF images were scanned at 400 dpi with an Epson Expression 10000XL scanner. OCR done with ABBYY Reader. JPG and PDF files were created for general use. |

| Language |

eng |

| Rights |

Public Domain. Courtesy of University Archives, Stewart Library, Weber State University |

| Source |

Archives LH1.A185 |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Setname |

wsu_olp |

| ID |

78090 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s6f0vpnv/78090 |