| Title |

Weber State College A Centennial History_1989 |

| Creator |

Weber State College |

| Contributors |

Sadler, Richard W., Editor |

| Description |

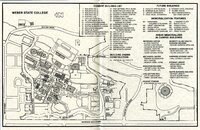

This monograph captures the history of the Weber State Institution for the first 100 years, as it evolved from Weber Stake Academy in 1889 to Weber State College in 1989. |

| Subject |

Faculty; Education, Higher; Ogden (Utah); Weber Stake Academy; Weber Academy; Weber Normal College; Weber College; Weber State College; Weber State College--History |

| Digital Publisher |

Stewart Library, Weber State University, Ogden, Utah, USA |

| Date Original |

1988 |

| Date |

1988 |

| Date Digital |

2012 |

| Item Size |

8.75 inch x 11.25 inch |

| Medium |

books |

| Item Description |

375 page hardback book |

| Spatial Coverage |

Ogden, Weber County, Utah, United States, http://sws.geonames.org/11788968, 41.22809, -111.96766 |

| Type |

Text |

| Conversion Specifications |

Archived TIFF images were scanned with an Epson Expression 10000XL scanner. OCR by ABBYY Reader. JPG and PDF files were then created for general use. |

| Language |

eng |

| Rights |

Public Domain. Courtesy of University Archives, Stewart Library, Weber State University |

| Source |

LD 5893.W52 W42 1988 Weber State University Archives |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s6pwjdwe |

| Setname |

wsu_hp |

| ID |

105719 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s6pwjdwe |

| Title |

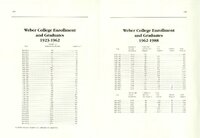

166_page 226 and 227 |

| Creator |

Weber State College |

| Contributors |

Sadler, Richard W., Editor |

| Description |

This monograph captures the history of the Weber State Institution for the first 100 years, as it evolved from Weber Stake Academy in 1889 to Weber State College in 1989. |

| Subject |

Faculty; Education, Higher; Ogden (Utah); Weber Stake Academy; Weber Academy; Weber Normal College; Weber College; Weber State College; Weber State College--History |

| Digital Publisher |

Stewart Library, Weber State University |

| Date Original |

1988 |

| Date |

1988 |

| Date Digital |

2012 |

| Item Description |

8.75 x 11.25 inch hardback. Pages number 1-375. |

| Type |

Text |

| Conversion Specifications |

Archived TIFF images were scanned at 400 dpi with an Epson Expression 10000XL scanner. OCR by ABBYY Reader. JPG and PDF files were then created for general use. |

| Language |

eng |

| Rights |

Public Domain. Courtesy of University Archives, Stewart Library, Weber State University |

| Source |

Archives LD 5893.W52 W42 2125 |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Setname |

wsu_hp |

| ID |

105860 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s6pwjdwe/105860 |