| Title |

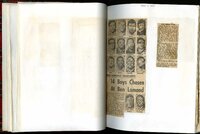

1967-1968 Ben Lomond High School Scrapbook |

| Creator |

Ben Lomond High School |

| Contributors |

Available through grant funding by the Utah State Library and the Institute of Museum and Library Services. |

| Description |

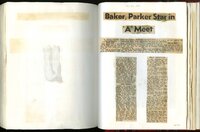

Since 1953, students at Ben Lomond High School have been creating scrapbooks. These books document the memories of the students each year. The scrapbooks hold a snapshot and time capsule of each student body. Each one contains photographs, newspaper articles and a written yearly history. |

| Subject |

Students--1960-1970; Education; Ogden (Utah); Ben Lomond High School (Ogden, Utah) |

| Digital Publisher |

Stewart Library, Weber State University |

| Date Original |

1967; 1968 |

| Date |

1967; 1968 |

| Date Digital |

2016 |

| Temporal Coverage |

1953-1999 |

| Item Size |

9 x 11.5 in. Hardbound scrapbook covered in red fabric with black, yellow, green, blue and white plaid pattern. 3.25 in. spine. |

| Spatial Coverage |

Ogden, Weber County, Utah, United States, http://sws.geonames.org/11788968, 41.22809, -111.96766 |

| Type |

Text; Image/StillImage |

| Conversion Specifications |

TIFF images were scanned at 400 dpi by Amy Higgs with an Epson Expression 100000XL scanner. OCR by Amy Higgs using ABBYY Reader. JPG and PDF files were then created for general use. |

| Language |

eng |

| Rights |

Digital image copyright 2016, Ben Lomond High School |

| Source |

Ben Lomond High School Library |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s69y99zm |

| Setname |

wsu_blhs |

| ID |

12118 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s69y99zm |

| Title |

Thistle Ben Lomond 68 - BenLomond_1967-68_287r |

| Creator |

Ben Lomond High School |

| Contributors |

Available through grant funding by the Utah State Library and the Institute of Museum and Library Services. |

| Description |

Since 1953, students at Ben Lomond High School have been creating scrapbooks. These books document the memories of the students each year. The scrapbooks hold a snapshot and time capsule of each student body. Each one contains photographs, newspaper articles and a written yearly history. |

| Subject |

Students--1960-1970; Education; Ogden (Utah); Ben Lomond High School (Ogden, Utah) |

| Digital Publisher |

Stewart Library, Weber State University |

| Date Original |

1967; 1968 |

| Date |

1967; 1968 |

| Date Digital |

2016 |

| Temporal Coverage |

1953-1999 |

| Item Size |

9 x 11.5 in. Hardbound scrapbook covered in red fabric with black, yellow, green, blue and white plaid pattern. 3.25 in. spine. |

| Spatial Coverage |

Ogden, Weber County, Utah, United States, http://sws.geonames.org/11788968, 41.22809, -111.96766 |

| Type |

Text; Image/StillImage |

| Conversion Specifications |

TIFF images were scanned at 400 dpi by Amy Higgs with an Epson Expression 100000XL scanner. OCR by Amy Higgs using ABBYY Reader. JPG and PDF files were then created for general use. |

| Language |

eng |

| Rights |

Digital image copyright 2016, Ben Lomond High School |

| Source |

Ben Lomond High School Library |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Setname |

wsu_blhs |

| ID |

15461 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s69y99zm/15461 |