| Title |

Weber Band Scrapbooks 1916-1967 |

| Creator |

Weber State College |

| Contributors |

Associated Students of Weber College |

| Collection Name |

Alumni Scrapbooks |

| Description |

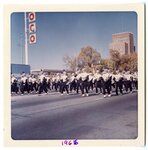

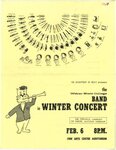

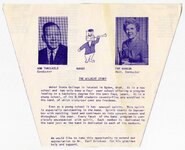

Scrapbooks with articles and images concerning Weber State University's Bands. |

| Subject |

Ogden (Utah); Weber College; Weber State College; Weber State University--History; Marching bands |

| Digital Publisher |

Stewart Library, Weber State University, Ogden, Utah, USA |

| Date Original |

1916; 1917; 1918; 1919; 1920; 1921; 1922; 1923; 1924; 1925; 1926; 1927; 1928; 1929; 1930; 1931; 1932; 1933; 1934; 1935; 1936; 1937; 1938; 1939; 1940; 1941; 1942; 1943; 1944; 1945; 1946; 1947; 1948; 1949; 1950; 1951; 1952; 1953; 1954; 1955; 1956; 1957; 1958; 1959; 1960; 1961; 1962; 1963; 1964; 1965; 1966; 1967 |

| Date |

1916; 1917; 1918; 1919; 1920; 1921; 1922; 1923; 1924; 1925; 1926; 1927; 1928; 1929; 1930; 1931; 1932; 1933; 1934; 1935; 1936; 1937; 1938; 1939; 1940; 1941; 1942; 1943; 1944; 1945; 1946; 1947; 1948; 1949; 1950; 1951; 1952; 1953; 1954; 1955; 1956; 1957; 1958; 1959; 1960; 1961; 1962; 1963; 1964; 1965; 1966; 1967 |

| Date Digital |

2019 |

| Temporal Coverage |

1916; 1917; 1918; 1919; 1920; 1921; 1922; 1923; 1924; 1925; 1926; 1927; 1928; 1929; 1930; 1931; 1932; 1933; 1934; 1935; 1936; 1937; 1938; 1939; 1940; 1941; 1942; 1943; 1944; 1945; 1946; 1947; 1948; 1949; 1950; 1951; 1952; 1953; 1954; 1955; 1956; 1957; 1958; 1959; 1960; 1961; 1962; 1963; 1964; 1965; 1966; 1967; 1968; 1969; 1970 |

| Medium |

scrapbooks |

| Item Description |

items in clear sheet protectors housed in a three inch white three ring binder |

| Spatial Coverage |

Ogden, Weber County, Utah, United States, http://sws.geonames.org/11788968, 41.22809, -111.96766 |

| Type |

Text; Image/StillImage |

| Conversion Specifications |

Archival TIFF images were scanned with an Epson Expression 10000XL scanner. JPG and PDF files were then created for general use. |

| Language |

eng |

| Rights |

Materials may be used for non-profit and educational purposes; please credit University Archives, Stewart Library, Weber State University. |

| Source |

Weber State University Archives |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s6fe2tqg |

| Setname |

wsu_scrap |

| ID |

11 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s6fe2tqg |

| Title |

1916 Band Scrapbook - 1916_65 018 |

| Creator |

Weber College |

| Contributors |

Associated Students of Weber College |

| Image Captions |

Scrapbooks with articles and images concerning Weber State University's Bands. |

| Subject |

Ogden (Utah); Weber College; Weber State College; Weber State University--History; Marching bands |

| Digital Publisher |

Stewart Library, Weber State University, Ogden, Utah, USA |

| Date Original |

2019 |

| Date |

2019 |

| Date Digital |

1916; 1917; 1918; 1919; 1920; 1921; 1922; 1923; 1924; 1925; 1926; 1927; 1928; 1929; 1930; 1931; 1932; 1933; 1934; 1935; 1936; 1937; 1938; 1939; 1940; 1941; 1942; 1943; 1944; 1945; 1946; 1947; 1948; 1949; 1950; 1951; 1952; 1953; 1954; 1955; 1956; 1957; 1958; 1959; 1960; 1961; 1962; 1963; 1964; 1965; 1966; 1967 |

| Temporal Coverage |

1916; 1917; 1918; 1919; 1920; 1921; 1922; 1923; 1924; 1925; 1926; 1927; 1928; 1929; 1930; 1931; 1932; 1933; 1934; 1935; 1936; 1937; 1938; 1939; 1940; 1941; 1942; 1943; 1944; 1945; 1946; 1947; 1948; 1949; 1950; 1951; 1952; 1953; 1954; 1955; 1956; 1957; 1958; 1959; 1960; 1961; 1962; 1963; 1964; 1965; 1966; 1967; 1968; 1969; 1970 |

| Medium |

scrapbooks |

| Item Description |

items in clear sheet protectors housed in a three inch white three ring binder |

| Spatial Coverage |

Ogden, Weber County, Utah, United States, http://sws.geonames.org/11788968, 41.22809, -111.96766 |

| Type |

Text; Image/StillImage |

| Conversion Specifications |

Archival TIFF images were scanned with an Epson Expression 10000XL scanner. JPG and PDF files were then created for general use. |

| Language |

eng |

| Rights |

Materials may be used for non-profit and educational purposes; please credit University Archives, Stewart Library, Weber State University. |

| Source |

Weber State University Archives |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Setname |

wsu_scrap |

| ID |

1738 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s6fe2tqg/1738 |