| Title |

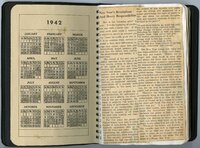

1942 Emily Almira C. Rich Diary B |

| Creator |

Rich, Emily A. C. (Emily Almira Cozzens), 1871-1954 |

| Description |

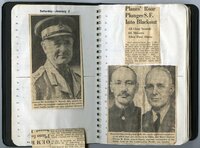

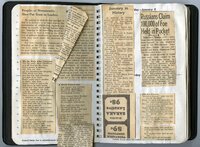

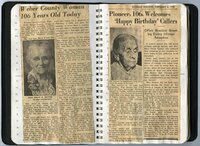

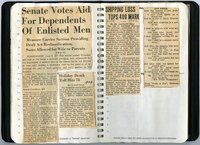

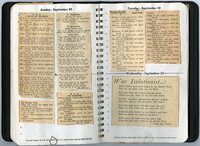

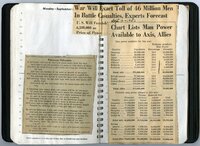

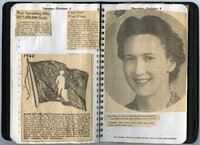

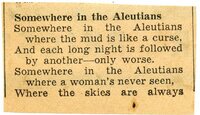

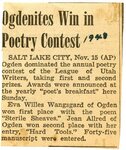

This collection contains 74 diaries of Dr. Edward Rich and his wife Almira. They begin in 1892 and run through 1965. The bulk of this collection centers on Almira's diaries that run from 1897-1947. During that time she documented her personal life and the medical practice of Edward, the community of Ogden and national events such as the outbreaks of WWI and WWII. The diaries also include newspaper and magazine clippings, memorabilia and pins. |

| Subject |

Diaries; Ogden (Utah); Rich, Edward I. (Edward Israel), 1868-1969; Rich, Emily A. C. (Emily Almira Cozzens), 1871-1954; Medicine--Utah--World War, 1914-1918; World War, 1939-1945 |

| Digital Publisher |

Stewart Library, Weber State University, Ogden, Utah, USA |

| Date Original |

1942 |

| Date |

1942 |

| Date Digital |

2011 |

| Temporal Coverage |

1868; 1869; 1870; 1871; 1872; 1873; 1874; 1875; 1876; 1877; 1878; 1879; 1880; 1881; 1882; 1883; 1884; 1885; 1886; 1887; 1888; 1889; 1890; 1891; 1892; 1893; 1894; 1895; 1896; 1897; 1898; 1899; 1900; 1901; 1902; 1903; 1904; 1905; 1906; 1907; 1908; 1909; 1910; 1911; 1912; 1913; 1914; 1915; 1916; 1917; 1918; 1919; 1920; 1921; 1922; 1923; 1924; 1925; 1926; 1927; 1928; 1929; 1930; 1931; 1932; 1933; 1934; 1935; 1936; 1937; 1938; 1939; 1940; 1941; 1942; 1943; 1944; 1945; 1946; 1947; 1948; 1949; 1950; 1951; 1952; 1953; 1954; 1955; 1956; 1957; 1958; 1959; 1960; 1961; 1962; 1963; 1964; 1965; 1966; 1967; 1968; 1969 |

| Item Size |

3.75 x 6 inch |

| Medium |

diaries |

| Item Description |

olive green spiral bound book |

| Spatial Coverage |

Ogden, Weber County, Utah, United States, http://sws.geonames.org/11788968, 41.22809, -111.96766 |

| Type |

Text |

| Conversion Specifications |

Archived TIFF images were scanned at 400 dpi with an Epson Expression 10000XL scanner. |

| Language |

eng |

| Relation |

https://archivesspace.weber.edu/repositories/3/resources/199 |

| Rights |

Materials may be used for non-profit and educational purposes; please credit the Special Collections Department, Stewart Library, Weber State University. |

| Sponsorship/Funding |

Funded through the generous support of the descendents of the Rich family; Edward I. Rich, Emily Almira Cozzens Rich |

| Source |

MS 74 Special Collections, Stewart Library, Weber State University |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s60a9pcx |

| Setname |

wsu_rich |

| ID |

84656 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s60a9pcx |

| Title |

056_Nurse Upsets Theories |

| Creator |

Rich, Edward I. (Edward Israel), 1868-1969; Rich, Emily A. C. (Emily Almira Cozzens), 1871-1954 |

| Description |

This collection contains 74 diaries of Dr. Edward Rich and his wife Almira. They begin in 1892 and run through 1965. The bulk of this collection centers on Almira's diaries that run from 1897-1947. During that time she documented her personal life and the medical practice of Edward, the community of Ogden and national events such as the outbreaks of WWI and WWII. The diaries also include newspaper and magazine clippings, memorabilia and pins. |

| Subject |

Diaries; Ogden (Utah); Rich, Edward I. (Edward Israel), 1868-1969; Rich, Emily A. C. (Emily Almira Cozzens), 1871-1954; Medicine--Utah--World War, 1914-1918; World War, 1939-1945 |

| Digital Publisher |

Stewart Library, Weber State University, Ogden, Utah, USA |

| Date Original |

1942 |

| Date |

1942 |

| Date Digital |

2011 |

| Item Description |

3.75 x 6 inch leather bound diary |

| Type |

Text |

| Conversion Specifications |

Archived TIFF images were scanned at 400 dpi with an Epson Expression 10000XL scanner. |

| Language |

eng |

| Relation |

https://archivesspace.weber.edu/repositories/3/resources/199 |

| Rights |

Materials may be used for non-profit and educational purposes; please credit the Special Collections Department, Stewart Library, Weber State University. |

| Sponsorship/Funding |

Funded through the generous support of the descendents of the Rich family; Edward I. Rich, Emily Almira Cozzens Rich |

| Source |

MS 74 Special Collections, Stewart Library, Weber State University |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Setname |

wsu_rich |

| ID |

90374 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s60a9pcx/90374 |