| Title |

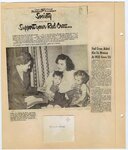

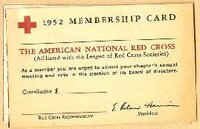

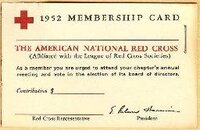

1950-1952_Northern Utah Chapter American Red Cross Scrapbook |

| Creator |

Northern Utah Chapter American Red Cross |

| Description |

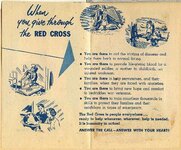

The Weber County Chapter of the Red Cross began in December 1915 when a small group of individuals gathered to begin organizing a chapter of the Red Cross. In 1962, the name was changed to the Bonneville chapter, and in 1969, the chapter merged with other chapters in Northern Utah to become the Northern Utah Chapter, with its headquarters located in Ogden, Utah. The scrapbooks range from 1940 to 2003 and highlight some of the important work of the Red Cross. The books include photographs, newspaper clippings, and other materials. |

| Subject |

American Red Cross. Programs and Services; Clippings (Books, newspapers, etc.); Correspondence |

| Keywords |

Porter, Maude Dee; McDonald, Madeline; Barton, Clara |

| Digital Publisher |

Stewart Library, Weber State University, Ogden, Utah, USA |

| Date Original |

1950; 1951; 1952 |

| Date |

1950; 1951; 1952 |

| Date Digital |

2018 |

| Temporal Coverage |

1940; 1941; 1942; 1943; 1944; 1945; 1946; 1947; 1948; 1949; 1950; 1951; 1952; 1953; 1954; 1955; 1956; 1957; 1958; 1959; 1960; 1961; 1962; 1963; 1964; 1965; 1966; 1967; 1968; 1969; 1970; 1971; 1972; 1973; 1974; 1975; 1976; 1977; 1978; 1979; 1980; 1981; 1982; 1983; 1984; 1985; 1986; 1987; 1988; 1989; 1990; 1991; 1992; 1993; 1994; 1995; 1996; 1997; 1998; 1999; 2000; 2001; 2002; 2003 |

| Item Size |

14.5x12.25x2.75 inch |

| Medium |

scrapbooks |

| Item Description |

This is a hard bound scrapbook with an exposed spine. The covers are cream with gold lettering. It has 147 pages and the content consists of hand lettered section pages, newspaper |

| Spatial Coverage |

Box Elder County, Utah, United States, http://sws.geonames.org/5771875; Cache County, Utah, United States, http://sws.geonames.org/5772317; Davis County, Utah, United States, http://sws.geonames.org/5773664; Morgan County, Utah, United States, http://sws.geonames.org/5778525; Rich County, Utah, United States, http://sws.geonames.org/5780377; Weber County, Utah, United States, http://sws.geonames.org/5784440 |

| Type |

Text; Image/StillImage |

| Access Extent |

183,478 KB |

| Conversion Specifications |

Archived TIFF images were scanned with an Epson Expression 10000XL scanner. OCR created by using ABBYY Fine Reader. JPG and PDF files were then created for general use. |

| Language |

eng |

| Rights |

Materials may be used for non-profit and educational purposes; please credit the Special Collections Department, Stewart Library, Weber State University. |

| Sponsorship/Funding |

Made available through grant funding provided by the Utah State Historical Records Advisory Board (USHRAB). |

| Source |

MS 462 Special Collections Department, Stewart Library, Weber State University |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s6gd38f8 |

| Setname |

wsu_arc |

| ID |

79326 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s6gd38f8 |

| Title |

1950-52_RedCross 214 |

| Description |

The Weber County Chapter of the Red Cross began in December 1915 when a small group of individuals gathered to begin organizing a chapter of the Red Cross. In 1962, the name was changed to the Bonneville chapter, and in 1969, the chapter merged with other chapters in Northern Utah to become the Northern Utah Chapter, with its headquarters located in Ogden, Utah. The scrapbooks range from 1940 to 2003 and highlight some of the important work of the Red Cross. The books include photographs, newspaper clippings, and other materials. |

| Subject |

American Red Cross. Programs and Services; Clippings (Books, newspapers, etc.); Correspondence |

| Type |

Text; Image/StillImage |

| Rights |

Materials may be used for non-profit and educational purposes; please credit the Special Collections Department, Stewart Library, Weber State University. |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Setname |

wsu_arc |

| ID |

80310 |

| Reference URL |

https://digital.weber.edu/ark:/87278/s6gd38f8/80310 |